and i chose america: censorship 2

This is probably a good place to distinguish between censorship and self-censorship. The distinction is crucially important, especially since appeals to decency and requests to treat all members of society as they want to be treated and to allow them equal and inclusive access to the same benefits regardless of their minority status, have been recklessly equated with and labeled as “censorship”. I mentioned in the preamble to this series that political correctness, for example, has often been dismissed in my home country of Romania as nothing more than another instance of censorship.

I vehemently opposed that parallel, as in my mind, censorship is a practice imposed by law and not something expected of individuals participating in society as a way to treat each other with respect and equanimity. Nevertheless, the parallel persists. What I’d call simple decency, many representatives of the European intelligentsia and of the political elites irresponsibly insist on calling and dismissing as “censorship”—as if almost incapable of critically discerning the danger thus created by enforcing stereotypes about ethnic and racial minorities, women, and other historically marginalized groups—thus emboldening with predilection in the second decade of the 21st century the revival of extremisms across Europe. The American conservatives, on the other hand, boisterously call the same phenomenon “cancel culture”. According to them, the very tenets of PC infringe upon the individual right of freedom of speech. While in theory, that may sound like an argument worthwhile considering, the practice shows that exposing young minds on campus, for instance, to unmitigated propaganda that promotes violence against other humans (see, for instance, cancelations of speaking commitments on university campuses of leaders of white supremacist or extremist movements) can lead to forfeiting the basic right to existence of members from the groups targeted by the said propaganda. So then, whose freedom trumps whose? In my mind, human society should have the ability, legislated or otherwise, to deny the creation of any sort of systemic structure that oppresses and leads to violence and elimination of fellow humans in the name of an ideology embraced by single or grouped individuals. And whatever ideology or whatever discourse ultimately leads to harm and potential destruction brought against any human must be promptly excluded from the public discourse, from the very fiber of civil society.

Now, official censorship, captured in the letter of the law, has truly been part of America, despite the appearance of freedom. Throughout its history, books in America have been banned in the name of preventing the spread of ideas such as gender and sexual orientation equality, anti-Christian values (understood broadly as pretty much everything that certain conservative Christian groups considered offensive), historical revisionism of core narratives of America (e.g., the sacrosanct nature of the founding fathers, manifest destiny, benevolence towards all, global savior, racial integration, melting pot), or, more recently, critical race theory. In the name of Christian morality, America has also developed an excessive concern for nudity in art and targeted it for censorship, and many scholars and activist organizations now make a point of tracking the numerous instances of such censorship.

As a writer, scholar, and journalist, the type of censorship I have encountered is, in many ways, more personal, albeit no less damaging for certain opportunities, either in life or career. For instance—and of course all this must be taken, again, as purely anecdotal and based exclusively on my own personal experience, as is the case with the rest of everything I write here—the first time I truly felt censored and my right to express my opinion diminished and ultimately silenced was within the confines of the unlikely space of academia. (Yes! Conservatives will likely exclaim joyfully feeling vindicated, as the American academia is one of the spaces where they believe that PC has mostly transitioned into censorship.) I was barely a few months into my doctoral program at the University of Chicago when, after a guest lecture on campus from a scholar of Japanese leftism, I tried to ask about her opinion on leftist literature in Japan in light of my own experience of politically engaged literature and the negative impact it had as a state propaganda tool during the communist dictatorship in Romania. I was barely done with my comment and question when I heard the voice of a colleague, a postdoctoral fellow at the university, call out loud above the heads of those in the packed room: “Now, we all must remember that George is from Romania!” For whatever reason, I felt an instantaneous wave of shame wash over me. My knees got weak, and I sat down almost unwillingly as I could no longer stand up.

All Romanians carry a burden: that of being Romanian. There isn’t anything that they can do about it, so they all carry in their own way. Some take to excessive nationalism and chest pounding. Others leave the country and never look back, refusing even to speak the language and maintain any connection with their roots. Others yet have adopted what I call the “ugly duckling” attitude and uncritically embrace every critique that comes their way about Romania and Romanians and make it their own, eager to prevent it from becoming about them and hoping that they can escape it. And finally, others, including myself here, as well as many people in my generation, decided to not be ashamed of who they are and where they come from, and to behave like any other European and global citizen with equal rights in the world. If anything, we chose to show through whatever we do and wherever we are that Romanians are in no way inferior (or superior) to any other modern nation. But I do admit that I was not interested in going to study in Europe because I didn’t want to deal with the prejudices and xenophobia I assumed I would encounter as a Romanian. So, to hear an American person someone call out in a room full of people, “George is from Romania” (and, as such, he and his comment are not to be taken seriously) was simply unfathomable to me at the time. I didn’t know where to put it. My whole premise that I wouldn’t face any sort of prejudice in America as a Romanian had shattered to pieces.

Whenever I look back on that crucial moment in my life in America, I become all the more convinced that what the female colleague said did not originate in some deeply-seated xenophobia (which I encountered on different occasions with disastrous consequences for my life—but, about that, later), but in an attempt to silence me and dismiss my veiled critique of leftist literature in Japan as irrelevant since I had grown up in a communist dictatorial regime. In essence, she was trying to censor me. That experience would have been perhaps forgotten if, over the next few years at the University of Chicago, I had not encountered the same attitude from the very people I respected and from whom I sought academic and research guidance: my academic advisors. I will never be able to forget the few instances in which my main advisor got extremely angry with me and indicated that if I didn’t agree with her position on the relevance of communist literature and activism, I was free to leave the program and that she was not willing to be told in her office of my experience of dictatorship Romania that contradicted her convictions. I learned not to argue, despite the fact that I thought the university space was the space for debate. My attitude in those first years of my doctoral program cost me quite a bit. I had three dissertation proposals rejected before having one approved for defense, so that I could finally be accepted to candidacy. It took me six years to become a doctoral candidate, and then five more to write and defend my dissertation. Those first six years, I realized later, were an attempt to make me quit the program because of my political views. I didn’t, although I did go to Japan at one point and did not return for three years, perhaps unconsciously seeking a respite, perhaps truly giving quitting a chance. I persevered and accepted all the support I could from family, colleagues, friends and other professors who were not as dogmatic in their views. In those first six years, I was also quietly pushed aside from joint research projects and publications, and none of my initiatives were supported, despite the fact that I was the recipient of a generous fellowship for the duration of my studies (and it is true that without that financial support I would have never been able to attend the University of Chicago. And for that, as well as for the essential lessons in humility I received and the profound intellectual and spiritual transformation I underwent during my doctoral studies there, I will forever be grateful).

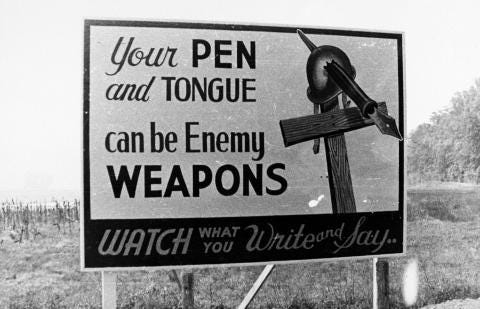

It was there, at the University of Chicago, that I learned to be careful what and when I say things. A few short years after having left Romania, I had returned to the very paradigm I hated, that in which I wasn’t able to freely express my point of view. And I am talking here about just that, “a point of view”! Not some dogmatic stance, not some political manifesto, not an incitement to hatred. An academic opinion, based on research and my own experience. I learned to be quiet and that heavy feeling in my stomach, the one like a rock in my gut returned, 6000 kilometers away from where I’d first encountered it.

For a while, I found refuge in writing opinion pieces in the Romanian media, the only safe way I could talk about America. But I was so used to writing in English too, and often felt that I needed to say things in English. So, I started a blog. Writing too turned out to be a problem. One time, when I was looking for jobs as an administrator in a public university and had submitted an application, I was surprised to receive a call from the human resources department of that university. I wasn’t even working there; I hadn’t even had an initial screening call with them. Yet, someone in their human resources department called me to let me know that although I was the top candidate for the position, they won’t possibly be able to even invite me for an initial screening call because someone in the office had looked at my blog and was appalled that one of my posts contained an image of an art installation/protest by a feminist artist in France which had a representation of a female nude. Shocked, I tried to explain to the human resources person that my article was a staunch and vigorous statement of support for the critique against misogyny that the artist was trying to express. That the very title of my blog post was expressing an anti-patriarchy and anti-misogyny position. It made, of course, no difference. The image (taken in one of the most important art museums of the world, mind you) was the only thing that mattered and the person/people in the office had declared themselves uncomfortable with it. As such, there was no way that I could ever be considered for the position. The HR person then proceeded to advise me to take the post down altogether and forget about the whole thing.

What do you think I did? I’m sorry to disappoint you, but I took it down. I published it later in Romanian translation and also wrote about the eerie experience with the HR person from that public university.

Other such events made me become even quieter, even more cautious and afraid. Ultimately, writing itself was no longer a refuge, so for a few years, I went completely quiet. Even poems I wrote were sometimes rejected because certain images made some editors or publishers uncomfortable. And I must admit here loud and clear: I really don’t want to make anyone uncomfortable. So, I stepped back.

The polarization of the political discourse in America after the Obama administration and the extraordinary partisanship that Trump’s presidency brought to the fore made things even more difficult. Even before Trump, everyone knew that you exposed yourself to criticism, negative comments, and threats if you dared touch the taboo topics: military, America’s historical narrative, nationalism, to name a few. Now the cavernous divide between the two political sides that have dominated America since its beginnings—conservatism and liberalism—made it virtually impossible to express any point of view. No space felt safe anymore. Whenever the two positions clashed, there was no more debate, but violent outbursts based on personal opinions. Dialogue and discussion were (and remain to this day) dead in America. Self-censorship all around. And with it, legalized censorship wherever legislation can be passed to set in stone any policy that prevents the other side from having a voice: banning access to vote, banning books, banning the teaching of concepts such as critical race theory or LGBTQ acceptance, and the list goes on quite a bit. Every possible ground where the other side can be limited and sidelined is now up for grabs. The sad thing is that, just like me, more and more people seem to make peace with all the types of censorship that they now have in their lives. And that is something I would have never imagined possible in America.

In the end, freedom of speech is coded in the American constitution, as the very first amendment. So, theoretically, anyone can publicly say anything. They can even write it down and publish it in the mass media. But that is only the theory. The practice shows that you must be willing to take sometime extreme risks especially when what you have to say goes against the grain or challenges certain dogmas. That freedom of speech can cost you dearly. And, rather than being a given, as you would imagine it in a functioning democracy where healthy debate and discussion take priority, it becomes an act of courage. For you never know who can be bothered by what you have to say on whichever side of the public opinion and political spectrum. And in America, a society where gun violence is but one of the ways in which citizens express their frustration, bothering someone who does not respect dialogue can amount to dire consequences. And while the old Romanian saying, “capul ce se pleacă, sabia nu-l taie” does have a fairly direct equivalent in English as “keep your head down and no harm will come to you”, another one in the same vein, but with another, no less devastating, consequence, “gura, că-ţi pierzi pâinea” should probably also have its own equivalent, something akin to “where the mouth stays shut, there’s bread in the hut”.

For someone like me, someone who prefers to stay away from isms, tough ideological stances and engaged doctrinaire stances regardless of their partisan endorsements, and who tightly adheres exclusively to the belief that humanity and its spirit must take precedence in human society, and for whom any ideology, from any side or angle of the political discourse, any belief in any god, any absolute certainty about superiority of any kind of one human over another that can lead to endorsement of and incitement to elimination of fellow humans is, and will forever remain, something that I won’t only never support, but I will oppose with all my might, in whatever way I am capable. I’m not sure what that makes me and those like me. Humanists? No, it’s a bit more nuanced than that, and it most likely doesn’t fit an ism, no matter how generous, how wide in its definition. And that, of course, escaping definitions as it were, makes things even more difficult for me and those like me because neither side can quite peg us to their satisfaction as either “with” or “against” them. And just when they think they have identified us as “liberals” or “leftists” or “Marxists” we come out in support of the tenets of capitalism and free market. And when then they then rush to call us “conservatives” or “ extremists” or “dictatorial” we indicate that we care about all humans and we believe that everyone should have free access to education, healthcare, and decent wages. As a result, I, and perhaps those others like me out there, end up rather quiet, afraid that we will be promptly censored by all parties and that we will inevitably upset everyone when we express our political position. But, maybe we should no longer be that quiet. We might be surprised by just how many voices we might be joined by once we speak a bit more loudly. (to be continued)